Wortmalerei: Ekphrasis (und Expressionismus)

Der Dialog zwischen Künstlern und Kunstwerken aus unterschiedlichen Genres ist uralt. Es gibt Gedichte, die sich auf Bilder beziehen und es gibt Skulpturen, die sich auf Legenden oder Romane beziehen. In der westlichen Tradition ist der für die poetische Beschreibung von Bildnissen heute gebräuchliche Begriff ‘Ekphrasis’[1] eng mit der platonischen Philosophie verbunden. Plato lässt Sokrates im Phaedrus folgendes sagen:

‘Weißt du, Phaedrus, das ist das merkwürdige am Schreiben, dass es tatsächlich der Malerei entspricht. Die Produkte des Malers stehen vor uns, als wären sie lebendig, aber wenn sie mit Fragen konfrontiert werden, bewahren sie eine majestätische Stille.’[2]

Das heißt vielleicht zunächst, dass das Gemälde (‘das Produkt des Malers’) erklärungs- bzw. deutungsbedürftig ist. Wenn es befragt wird, ist es nicht in der Lage, von sich aus zu antworten; es bleibt auf erläuterende ebenso wie ver-antwortende Worte zu Inhalt, Kontext und Autorschaft angewiesen. Die Deutung oder Interpretation des Bildes geschieht zumeist in Sprache, durch gesprochene Worte oder Texte.

Wer das Argument im Phaedrus jedoch weiter verfolgt, erkennt, dass Plato umgekehrt auch den Worten eine Selbstbefangenheit und sogar einen Bedeutungsmangel bescheinigt. Und damit verweisen die Worte wieder zurück auf Bilder, Urbilder, Ideen und bildhafte Aktionen. Je für sich genommen sind also die Medien Bild und Sprache zum Verständnis ungenügend. Erst im interaktiven Dialog von Bild und Wort, Auslegung und Erscheinungsformen ergibt sich möglichenfalls künstlerischer Sinn.[3]

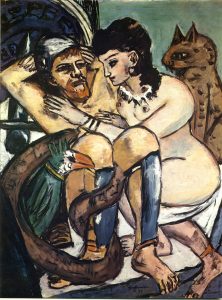

Max Beckmann, Odysseus und Kalypso, 1943

In einem modernen und spezifischer definierten Sinne bedeutet ‘Ekphrasis’ ein Gedicht, das ein Bild oder eine Skulptur beschreibt. Ich möchte hier zwei eigene Versuche, die sich auf expressionistische Malerei beziehen, etwas näher erläutern. Der erste erschien unter dem Titel ‘Max Beckmann, Odysseus and Kalypso’ in dem amerikanischen Lyrikmagazin IthacaLit:

Max Beckmann, Odysseus and Kalypso 1943

This is the man who prefers mortality

to eternal compromise.

This is the woman who prefers vitality

to compromised eternity.

This is the woman who charms

the serpent and to whom wise birds minister.

This is the man who blindfolds

pudent cyclops and bails out some friends.

This is the man who knows sirens;

tied to the foremast, he resists

bribes, destroyers of the polis.

This is the woman who knows gods

hate demigods falling in love with mortals,

hate the happiness of women and men.

The woman, naked

except for her feather necklace,

the cat’s coat

(and the ankle chain).

The man, naked

except for the iron shin-guards

and the iron helmet of his armor.

Here they are in Amsterdam, 1943

starving so they can afford

the blue paint for their aura

of pain and hope.

And they read that she gives him bread,

wine, and wood for the raft of his journey;

words of love

for a seven-year farewell.[4]

Max Beckmann, Odysseus und Kalypso 1943

Dies ist der Mann, der Sterblichkeit

ewigem Kompromiss vorzieht.

Dies ist die Frau, der Lebendigkeit

über kompromitierte Ewigkeit geht.

.

Dies ist die Frau, der Schlangen

und weise Vögel zu Diensten sind.

Dies ist der Mann, der Sirenen

widersteht, an den Vormast gebunden,

Schmeichlern, Zerstörern der Polis widersteht.

Dies ist die Frau, die weiß, die Götter hassen

Halbgötter, die sich in Sterbliche unsterblich verlieben, hassen menschliches Glück.

Die Frau, nackt

bis auf ihr Feder-Halsband,

die Katze im Fell

(und die Fußketten).

Der Mann, nackt

bis auf Reste

der Rüstung: blankes Eisen

übers Schienbein geschnürt.

Da liegen sie nun,

einander bis zur Kenntlichkeit

unbekannt, 1943 in Amsterdam

und sparen sich das Blau ihrer Aura

vom Munde ab, ihrer Aura

aus Hoffnung und Schmerz.

Und sie lesen, sie gebe ihm Wein,

Brot und Holz für das Floß auf die Reise;

Worte der Liebe

zum siebenjährigen Abschied.

Das Gedicht bezieht sich auf ein Bild in der Hamburger Kunsthalle, Max Beckmanns ‘Odysseus und Kalypso’. Das Bild wurde 1943 im Amsterdamer Exil unter Bedingungen extremer Entbehrung geschaffen, denn Beckmann war vor den Nazis aus Deutschland geflohen, die seine expressionistische Kunst als ‘entartet’ verspotteten und verfolgten. Das Gedicht versucht, das Gemälde durch Bildbeschreibung sowie Anspielungen auf Homers Epos und Beckmanns Biographie zum Sprechen zu bringen, dem bildlichen Expressionismus in poetischer Sprache zu antworten. Das Gedicht steht damit eigentlich sogar in einer doppelten Ekphrasis-Reihe: Beckmanns Bild bezieht sich auf die Odysee, den Ur-Text Homers. Das Gedicht wiederum bezieht sich auf Beckmanns Illustration des Epos. Der ekphratische Diskurs umfasst damit eine Zeitspanne von ungefähr 2750 Jahren.

Die Motive: der durch den Krieg Exilierte und die tragische Liebe im Exil, die auch für die Spannung einer multikulturellen Geflüchteten-Identität steht. Der Arche-Typ: Odysseus, der seine kriegszerstörte Herkunftswelt verlässt, im Mittelmeerraum umherirrt, und sich auf auf der Insel Ogygia in Kalypso verliebt. Sieben Jahre lang versucht sie, ihn zu halten, aber er träumt von der alten Heimat und seiner Frau Penelope ud kehrt am Ende mit Kalypsos Hilfe nach Ithaca zurück. Diese Themen sind – gerade wieder – und nicht nur in der westlichen Geschichte aktuell.

Ich hatte das Gedicht zur Veröffentlichung nach Ithaca, einer Universitätsstadt in Up-State New York gesandt, die nach Odysseus’ Heimatort benannt ist, weil ich dort einen alten Freund hatte. Ich hatte das Privileg, H. Peter Kahn 1985 in Hamburg kennenzulernen, wo er Programmdirektor des Cornell University Studies Abroad Programm war. Ein Exilierter auch er. Als Kind war Peter Kahn mit seiner Familie, die mit der Familie Gustav Mahlers verwandt war, vor den Nazis in die USA geflohen. Wie Max Beckmann, der von 1948 bis 1950 in den USA, vor allem in St. Louis und New York lebte, war auch Peter Kahn ein expressonistischer Maler: https://hpeterkahn.org/.

An der Cornell University wurde Peter Kahn 1957 Professor und machte sich dort als Polyhistor und inspirierender Lehrer und Mentor schnell einen Namen. Er war ein Experte u.a. in Kunstgeschichte, Philosophie, vergleichender Literatur, Zeichnen und Malen, Graphikdesign, Buchausstattung, Kaligraphie und Musiktheorie. Auf seinen sommernächtlichen Parties tummelten sich über seinem legendären Punsch die Glühwürmchen und seine amerikanischen Studierenden wie Thomas Pynchon (der enigmatische Autor von Gravity’s Rainbow), Richard Fariña und Michael Curtis, der Literatur-Editor des The Atlantic Monthly. Ich war 1985 noch Student in Hamburg und arbeitete als Reiseführer für internationale Studierende und als Tutor für das Cornell Programm in Hamburg. Peter Kahn und seine Frau, die Kinderbuchautorin Ruth Stiles Gannett (My Father’s Dragon) waren während dieser Zeit des späten Kalten Krieges aktiv in der deutschen Friedensbewegung engagiert. Im dritten Stock des Gästehauses der Universität Hamburg gab es die schönsten Dinner-Parties mit selbstgeschabten Spätzle (Peter kam ursprünglich aus Schwaben) und die engagiertesten politischen und kulturellen Diskussionen weit und breit.

Gemeinsam mit Ruth und Peter organisierte ich Bildungsreisen für internationale Studierende. Besonders eindrucksvoll war es, wenn Peter in Museen, Hörsälen oder den Frühstücksräumen der Jugendherbergen über die Kunst der vertriebenen Expressionisten sprach. Er hatte viele von ihnen persönlich gekannt. Auf den Kunstreisen hatten die meisten eine Kamera dabei. Peter jedoch nicht; er reiste nie ohne sein Skizzenbuch. Und er ermunterte seine Kunstgeschichtsstudenten, und auch mich damals, selbst zu zeichnen. Es ging ihm, in der Tradition Goethes, um eine ‘eigenhändige Anverwandlung’ des Gesehenen und Erlebten. Ich habe seitdem immer wieder ein Skizzenbuch auf Reisen dabei. Es ist zugleich ein Notizbuch für ekphratische Aufzeichnungen. Es muss in den USA und in Europa eigentlich eine kleine, von Peter angeregte ‘Turm-Gesellschaft’ von Skizzenbuch-Trägern geben.

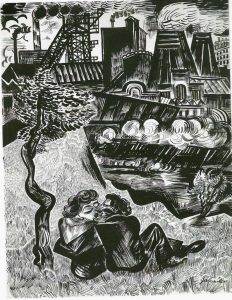

Das zweite Beispiel von Ekphrasis gilt dem Gesamtwerk (nicht einem einzelnen Bildwerk) des Malers Conrad Felixmüller:

Für Conrad Felixmüller

Dein Regen macht

den Herbstwald bunt,

du malst Gesichter

aus Brikett und Not,

ein alter Kirschbaum

trägt den Farbenschlund.

Die Schlote quellen,

röchelnd im Bach Forellen,

den Liebenden schlägt keine Stund.

Leiber, Seelen stehn

am Abgrund, Gerstenhocken

müd und beinah unerschrocken.

Holzschnittaugen schaun

den Tod. Druckfeucht

und schwarz. Wie Chemnitz

oder Engelsbrot.

Conrad Felixmüller (1897–1977) war ebenfalls ein Pionier des Expressionismus. Zu Weihnachten bekam mein Vater immer Weihnachtskarten von seinem Sohn Titus Felixmüller nach Vorlagen von Gemälden seines Vaters, die bis Ostern auf dem Bücherbord im Wohnzimmer stehen blieben. Titus Felixmüller war als junger Architekturstudent Assistent in NS-Architekturprojekten, u.a. um Hitlers Stararchitekten Speer. Vielleicht auch, um das Leben seines Vaters Conrad, der Kommunist war, zu schützen. Nach dem Krieg spezialisierte sich Titus auf den Bau von Bürobauten und Krankenhäusern.

Conrad Felixmüller stellte in seinen Bildern immer wieder die Welt der Bergarbeiter und marginalisierten Künstler in Sachsen dar. Er fand deshalb in der westdeutschen Kunstszene nach dem Krieg wenig Beachtung; dort war man – sich atlantisch-avangardistisch orientierend – dabei, der abstrakten Malerei und dem Happening mehr Raum einzuräumen. Die Nationalsozialisten hatten über 150 von Conrad Felixmüllers Werken zerstört. 1944 verlor er sein Atelier bei einem Bombenangriff auf Berlin. In Ostdeutschland wurde er zwar 1949 Professor in Halle/S.; aber auch in der DDR gehörte er nicht zu den intensiv geförderten Künstlern, denn er übte wiederholt Kritik an stalinistischen Interpretationen eines ‘sozialistischen Realismus’ und an diversen Bonzen.[5]

Das Gedicht ist eine Hommage auf Conrad Felixmüller, einen Meister der Farben wie auch der Schwarz-Weiß-Kontraste des Holzschnitts. Es ist eine Erinnerung an einen zu Unrecht ins Abseits geratenen Moderne-Künstler, der dennoch in seinen Motiven immer wieder auch bewusst Anregungen in der Tradition suchte. So zählen zu seinen schönsten Arbeiten Porträts von spielenden Kindern und von Liebenden: Verträumter Expressionismus. Oft bewegen die Liebenden sich vor Hintergründen, die wie viele Industrieregionen in Mittel- und Süddeutschland, Nord- und Mittelengland, Nordfrankreich oder Belgien aus einer Mischung von kleinräumigen Agrarlandschaften und gigantischen Fabrikanlagen und Bergwerken bestehen. Conrad Felixmüller malte diese Landschaften, ohne sie zu romantisieren oder zu beschönigen, aber auch, ohne sie zu dämonisieren. Sein emphatischer Blick galt dabei immer auch den Beziehungen der Menschen in diesen hässlich-schönen Industrie- oder Agrarräumen; manchmal geht er in einen manieristischen sozialen Realismus über, wie man ihn ähnlich auch bei dem englischen Zeitgenossen Stanley Spender und später dem Australier Robert Dickerson finden kann.

Um den Bogen noch einmal zurück zu Plato zu schlagen. Fraglos erschließt sich ein großer Teil der in den Gemälden ausgedrückten Emotionen unmittelbar beim Betrachten. Aber die gefühlten Eindrücke und Bilder gewinnen durch historische und kulturelle Nachfragen und die dichterischen Worte der Ekphrasis und der Analyse vielleicht noch einen weiteren, oft aktualisierenden Kontext und ermöglichen vertiefte Einsichten. In zeitgenössischen, postmodernen Zusammenhängen, hat W. J. T. Mitchell uns daran erinnert, dass “alle Medien gemischte Medien (‘mixed media’) [sind]. Das bedeutet: die Vorstellung vom Medium und von Vermittlung erfordert notwendig, sie als eine Mischung aus sinnlichen, begrifflichen und semiotischen Elementen anzusehen.”[6] Und mit den poetischen Formen, Erklärungen und persönlichen Geschichten ändert sich dann auch noch einmal der Blick auf die Bilder. Gegebenenfalls im Sinne der Realisierung, dass wir uns in einem vielschichtigen Vermittlungsgefüge bewegen, das sich im Idealfall aus verständnisvollen Dialogen ergeben mag. Das Bildnis verbindet Eindruck und Ausdruck, Gemaltes und Wortmalerei.

Dr. Norman P. Franke (MA Hamburg, PhD Humboldt, Berlin) ist ein in Hamilton, Neuseeland lebender Dichter, Zeichner und Hochschullehrer. Er ist Research Fellow der australischen University of Newcastle, NSW.

[1] Der Begriff stammt aus dem Altgriechischen: ἐκ ek (‘hervor, aus’ ) and φράσις phrásis (‘sprechen’), das Verb ἐκφράζειν ekphrázein, bedeutet ‘bezeichnen’ oder ‘einem Objekt einen Namen verleihen’.

[2] Platon, Phaedrus 275d, Übersetzung N.P.F.

[3] Angemerkt sei hier noch, dass Plato sich in seiner Erkenntnistheorie ganz besonders auf den visuellen Sinn und sein Verhältnis zu Wort, Begriff und Idee konzentriert; die anderen Sinne, Gehör, Geschmack, Geruch und Gefühl dabei aber vernachlässigt.

[4] http://www.ithacalitarchives.com/autumn-2019.html Ich zitiere hier zunächst die publizierte englische Fassung, die von der nachfolgenden deutschen geringfügig abweicht.

[5] Mössinger, I. And Bauer-Friedrich, T. (ed.) Conrad Felixmüller, Zwischen Kunst und Politik. Chemnitz: Wienand Verlag 2012

[6] W. J. T. Mitchell, ‘There are no visual media’ In: W. J. T. Mitchell, Image Science: Iconology, Visual Culture, and Media Aesthetics. Chicago, London: Chicago University Press. p. 129